Missile vs. Laser: The Game of Terminal Maneuvers

01-07-2025 9:42PM (ET) 02-06-2025 6:54PM (ET) (edited)

Missile vs. Laser: Terminal Maneuvers the Game

What is the best strategy to hit a maneuvering missile with a point defense laser when the missile is traveling through space at ~1 percent the speed of light?

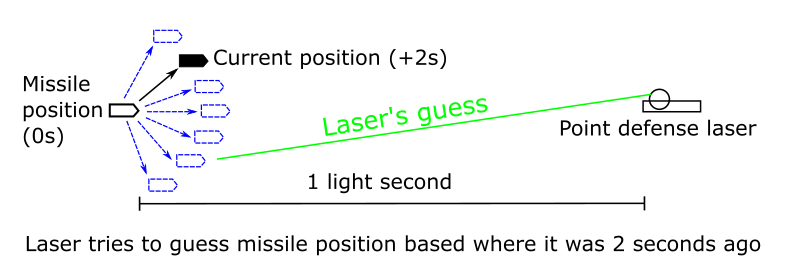

A few years ago I was trying to work out at what range a point defense laser on a spaceship could destroy a missile traveling toward that spaceship at ~1% the speed of light1. As I did the math on beam waist, divergence, focal point and power it became clear that the limiting factor on effective range wasn't any of these. At 1 light second the laser only learns where the missile was a second ago and the laser itself takes an additional second to reach the missile. This creates a 2 second latency. The missile can burn maneuvering fuel to do random but minor course changes to make its future position uncertain to the laser. Thus the laser could hit the missile, if only it knew where the missile was going to be4.

I assumed this would be a simple calculation. Determine the sphere of possible locations the missile could be based on the maximum power of the thrusters on the missile. As the missile gets closer, the latency decreases, which causes this sphere of possible locations to shrink. Given the size of sphere over time, we can determine the total probability the laser hits the missile before the missile gets close enough to detonate2 and destroy the ship the laser is on.

However the power of the thrusters on the missile depends on how much maneuvering fuel it burns and the amount of fuel on the missile is finite. This produces the following effect:

- The missile wants to make its future position uncertain by burning fuel.

- If the missile is far away from the laser, burning small amounts of fuel can make the position of missile very uncertain to the laser.

- When the missile gets closer to the laser, the latency to the laser decreases, so it costs the missile more fuel to maintain that same level of uncertainty.

These rules suggests a strategy where the missile conserves fuel when it is far away and then burns increasing more fuel as it gets closer. This approach is still missing a critical aspect.

Consider the following simple game. The missile either burns 1 or 2 units of fuel. The laser attempts to guess how much fuel the missile burned. If the missile burns 1 fuel and the laser guesses 1 fuel, the missile is destroyed. If the missile burns 2 fuel and the laser guesses 2 fuel, there is only 1/2 chance the missile is destroyed since burning more fuel maneuvering makes it harder for the missile to be hit by the laser. This is a zero-sum game, if the laser wins, the missile loses, if the missile wins, the laser loses.

| Laser guesses 1 Fuel | Laser guesses 2 Fuel | |

|---|---|---|

| Missile burns 1 Fuel | 1 (Laser wins) | 0 (Laser Loses) |

| Missile burns 2 Fuel | 0 (Laser Loses) | 1/2 (Laser wins half the time) |

We can represent all missile strategies using the variables, m1,m2,l1,l2, where m1 is the probability the missile chooses 1 fuel, m2 is the probability the missile chooses 2 fuel. The probability the laser wins given a missile strategy (m1,m2) and laser strategy (l1,l2) is:

lwins=m1⋅l1+1/2⋅m2⋅l2

If we assume the laser always knows the strategy the missile will use, what strategy should the missile use? If the missile always burns 2 fuel to be safe, (m1=0,m2=1), the laser knowing this always guess 2 Fuel (l1=0,l2=1) resulting in the probability the laser wins 0⋅0+1/2⋅1⋅1=1/2.

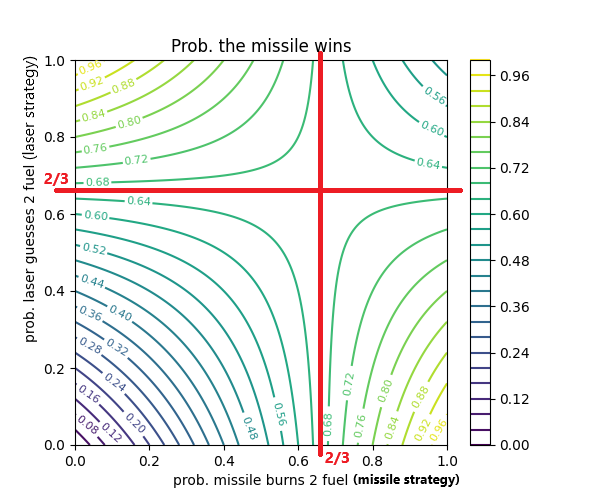

If the missile burns 1 fuel 1/3 of time and 2 fuel 2/3 of the time, (m1=1/3,m2=2/3). It doesn't matter what strategy the laser chooses, the laser win probability will be: 1/3⋅1/3+1/2⋅2/3⋅2/3=1/9+4/18=1/3.

A better strategy for the missile is to burn 1 fuel 1/3 of time and 2 fuel 2/3 of the time, (m1=1/3,m2=2/3). Under this strategy it doesn't matter what strategy the laser chooses, the laser win probability will be: 1/3⋅1/3+1/2⋅2/3⋅2/3=1/9+4/18=1/3. and if the laser wins 1/3 of the time, the missile wins 2/3 of the time. This is also true in the other direction, if the laser uses this strategy, guessing 1 fuel 1/3 of the time and 2 fuel 2/3 of the time, it will always win 1/3 of the time regardless of what strategy the missile chooses. This property of a game is called a Nash Equilibrium. We graph it below. Notice the line for 2/3 is the same for all strategies.

If the missile always burns the same amount of fuel and the laser knows this, the laser has to search a smaller area. Put another way the missile is more likely to win if it occasionally chooses the worst option, making the wrong play at the right time.

LANCEY:

Gets down to what it's all about, doesn't it?

Making the wrong play at the right time.

THE KID:

You were crazy -- odds are three hundred to one against.

LANCEY:

(after a moment)

I don't play a percentage game. I play stud poker my way.

And I got the money and you got the questions.

In an attempt to explore the strategy of this missile vs laser dynamic I designed a game called terminal maneuvers. It is more complex than the single round variant we just looked at but attempts to be as simple as possible. First I'm going to describe the rules, then look at how to play it with some dice, cards and a piece of paper and then finally provide a link to a playable online version I wrote.

How to play Terminal Maneuvers

In this game there are two players, a missile and a laser. The game consists of five rounds. The laser's goal is to hit the missile with the laser before the end of round five. The missile's goal is to survive to end of round five.

At the beginning of each round the missile secretly chooses how much fuel to burn to maneuver. Then the laser attempts to guess this number. We assume the laser always knows how much starting fuel the missile has remaining at the beginning of each round.

If the laser guesses incorrectly. The missile is safe for that round and we go to the next round.

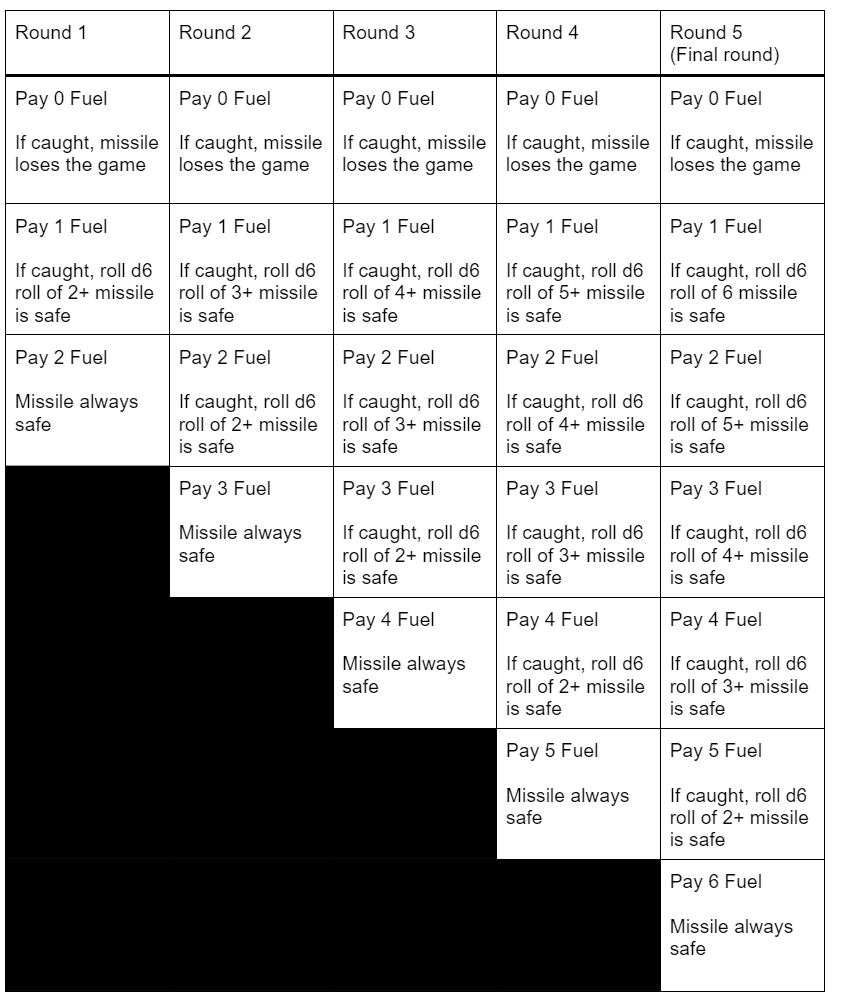

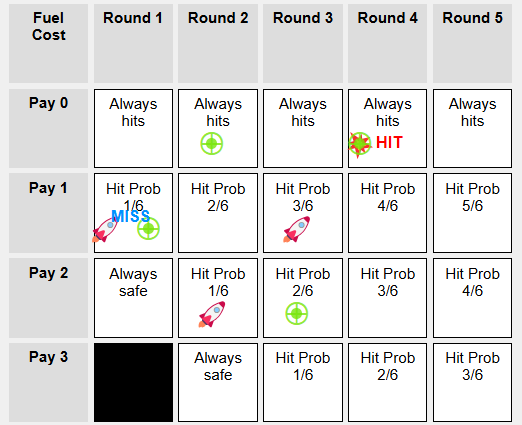

If the laser guesses correctly, there is a hit probability table based on the amount of fuel the missile burned and the round. Burning more fuel produces a larger potential area that missile could be in and thus it is less likely the laser hits the missile. On the other hand as the missile gets closer to the laser, the lasers information about the missile is more recent and thus, the hit probability goes up.

| Fuel burned | Round-1 | Round-2 | Round-3 | Round-4 | Round-5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 Fuel | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 Fuel | 1/6 | 2/6 | 3/6 | 4/6 | 5/6 |

| 2 Fuel | 0 | 1/6 | 2/6 | 3/6 | 4/6 |

| 3 Fuel | 0 | 0 | 1/6 | 2/6 | 3/6 |

| 4 Fuel | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/6 | 2/6 |

| 5 Fuel | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/6 |

| 6 Fuel | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The values for each pair (round, fuel burned) are the probability the laser will hit the missile, if the laser guesses the fuel spent correctly. We use x/6 so the game can be played with a d6 (six sided dice). If in round 1, the laser guesses 1 fuel, then roll a d6 to determine if the laser hits the missile. The value 1 represents that if the laser guesses correctly, the laser always hits. The value 0 represents that even if the laser guesses correctly it will always miss.

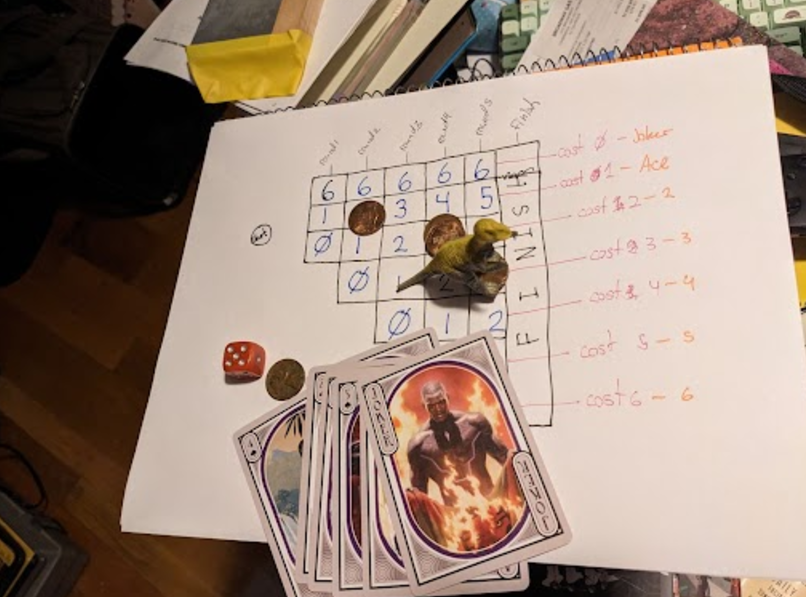

Playing it like a Board Game

The game requires

- 7 pennies representing the missile’s fuel,

- A d6 die,

- 7 cards,

- The game board

Game Board

Cards

- Guess Missile burns 0 Fuel

- Guess Missile burns 1 Fuel

- Guess Missile burns 2 Fuel

- Guess Missile burns 3 Fuel

- Guess Missile burns 4 Fuel

- Guess Missile burns 5 Fuel

- Guess Missile burns 6 Fuel

To substitute playing cards, choose seven playing cards, assign each one of the seven a number from 0 to 6. King=0, Ace=1, 2=2, 3=3,...

Rules

The game takes place on the board provided below. The laser always has a hand of 7 cards. The missile starts with 6 fuel.

Each round

- The laser starts the round by playing one of its seven cards face down. This is the laser's guess of how much fuel the missile will burn.

- Then, the missile chooses how much fuel it will burn in that round and reduces its remaining fuel by that amount.

- Once the missile has decided how much fuel it wants to spend, the laser flips over the card it played face down. If the laser guesses correctly, the missile is caught. Then roll a d6, if appropriate to determine if the missile loses the game.

- If roll determines that the missile is not safe, the missile loses the game.

- The laser then returns the played card to their hand and the next round starts.

- If Round 5 has ended and the missile has not lost the game, the missile wins and the laser loses.

Additional notes

- The missile can not have negative fuel. If the missile has 0 fuel it no longer has any options and must pay 0 fuel in all future rounds.

- The laser always has all seven cards in their hand.

- When we say ”roll a d6 on a 4+ missile is safe, we need on a roll of 4, 5, or 6, the missile is safe” and all other outcomes the missile loses the game.

- It is pointless for the laser to ever guess a fuel amount in which the missile is always safe. For instance if the laser guessing correctly 2 fuel in round 1 the laser still don't hit. The laser wasted its guess.

As a Video Game

You can play terminal maneuvers against a computer. The code is available on github.com/ethanheilman/terminal-maneuvers.

Why Start with Seven Fuel

If the missile has 20 or more fuel, it will always win since it can always spend enough fuel in each round to be completely safe, e.g. spending 2 fuel on round one, 3 fuel on round two, ... 6 fuel on round 5.

If the missile has 4 or less fuel, it will always lose. The laser's strategy should be to guess 0 fuel in each round. Thus, if the missile in any round burns 0 fuel, it will be hit. This means to win the missile must burn at least 1 fuel per round. Since there are 5 rounds, the missile will have 0 fuel remaining in round 5 and so must burn 0 fuel. The laser knows the missile must burn 0 fuel, because that is the only option left. This means the missile is always hit.

So given a fuel value between 5 and 19, the missile and laser both have a chance of winning. The missile's chance of winning increases as the starting fuel goes up.

Generally I play the game where the missile has 7 fuel. So far in my experiments the laser wins ~75% of the time.

Accuracy

Terminal maneuvers tries to get at the core strategy elements here so that the player can get a sense of the trade-offs and the strategic landscape. It is not a high fidelity simulation. Terminal maneuvers suffers from a number of inaccuracies:

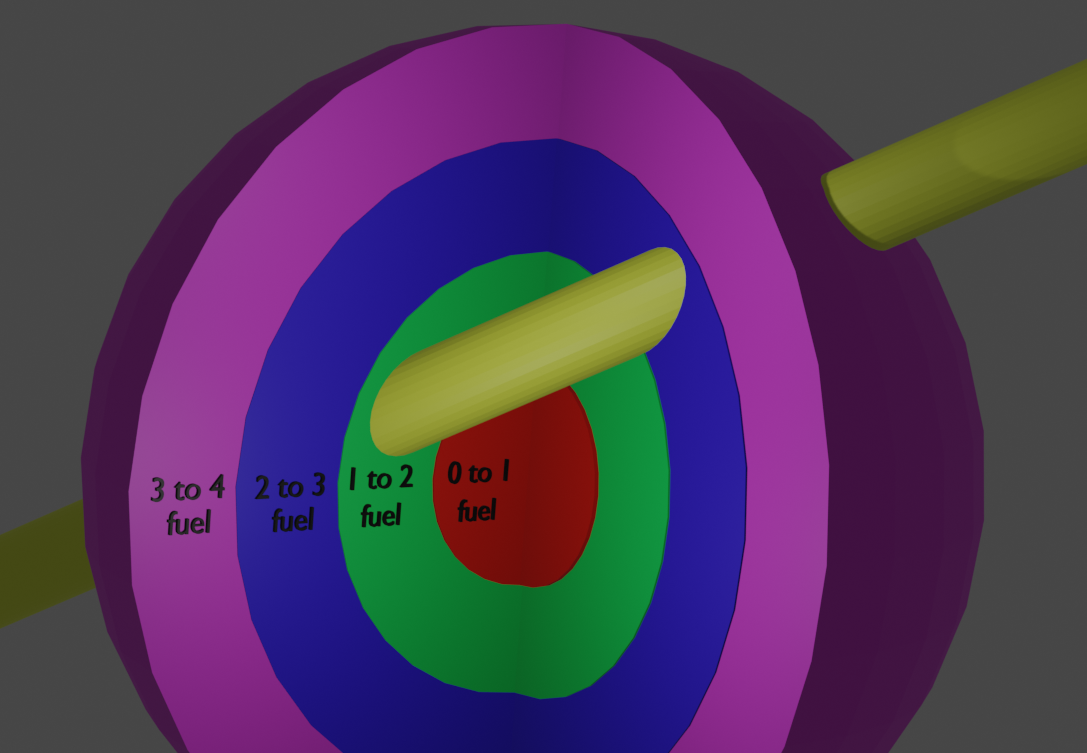

Hit Probability is Extremely Simplified

The actual increase in uncertainty for burning fuel is tricky to calculate. At a particular distance each unit of fuel provides 10 meters of movement we can think of this as a series of spherical shells. If the laser guesses the missile burned 0 to 1 Fuel, the missile must be somewhere in a 10 meter radius sphere. If the laster guesses the missile burned 1 to 2 Fuel, the missile must be somewhere 20 meter shell where the shell is 10 meters thick. As the area of a sphere of radius r is 4π˙r2 the equation for the area the laser needs given f is 4π(10×f)2−4π(10×f−1)2 where f a range of fuel burned between f−1 to f, e.g., f=4 means between 3 to 4 units of fuel was burned. Comparing the actual area against the d6 hit table shows that d6 only roughly approximates the probability differences.

| f | Area | Hit prob. in game |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | ~1256 | 5/6 |

| 2 | ~3770 | 4/6 |

| 3 | ~6283 | 3/6 |

| 4 | ~8796 | 2/2 |

| 5 | ~11310 | 1/6 |

| 6 | ~13823 | 0 |

However the area of the shell is not an accurate measure of hit probability. This is because the laser can pass through multiple shells at once (as shown). Some areas in a shell provide less protection than others because the laser gets them for free, hitting many different potential missile locations with a single laser.

Laser should be resource constrained

In reality the laser does not get infinite shots, firing a laser of the power required draws enormous of power and generates enormous amounts of heat. Dissipating heat in the vacuum of space is difficult. A more realistic game would model the laser's resources constraints as well as the missile's fuel.

I thought about adding this to the game by giving the laser have a "skip turn" card that it must play at least once instead of a guess. If the laser is still holding the "skip turn" card by the last turn, the missile wins automatically since the laser must play that card (essentially running out of shots early). I avoided putting this in the game because to my mind the best time to play such a card is on the first turn because the laser has the worse odds on the first turn.

In some way the game does model the laser being resource constrained in that the game only has has only 5 rounds. If the laser has 5 shots then the game could be viewed as having 6 rounds, but the laser always skips the 6th round since the laser is waiting until the missile was closer to use up a shot. That said, maybe I'm wrong here, perhaps the laser should be allowed to the "wrong thing at the right time." The game currently favors the laser, forcing it to skip one turn might make the game more balanced.

Reality is continuous

The turn based and integer nature of the game makes it is easy to play with dice and simply to think about but it probably introduces significant artifacts.

One way I've played around with making this continuous is to define the missile and laser strategies as continuous functions. The missile strategy, m(t)→f would take the current time t and would output the fuel to burn f in that instant. The laser strategy l(m(t-λ)) gets the output of the missile function given the current latency λ. To ensure the missile strategy and laser strategy is randomized, we'd define them as being randomly sampled from a family of strategies.

Missile Swarms

It seems unlikely to me that a single missile would be used. For instance if a single missile has a 1/10 chance surviving an destructing the ship protected by the missile then the probability two missiles destroy the ship is better than 1-(1-1/10)*(1-1/10)=19/100. While one of the missiles is being targeted by the laser the other missile also getting closer. This means that by the time the first missile is destroyed the second missile has a much better chance since it has covered most of the distance.

Even worse for the laser, a large missile swarm is likely to contain missiles whose sole purpose is dazzling and jamming the laser's sensors. Further complicating the laser's ability to target any of the missiles.

I didn't include missile swarms in the game since I suspect that many of the things that make the game interesting would average themselves out. For instance each missile could just burn a small amount of maneuvering fuel to get the volley close enough to so that a hit was guaranteed.

Future work

To my shame, I haven't actually done the work to see if there is a Nash equilibrium between the missile and laser strategies although I know someone who has looked in it and may publish results later. It would be fun to do a continuous version of the game where people could submit missile and laser strategies and create a leader board.

Final thoughts

I've been playing around with this game off and on for a few years, with slightly different rules. If you find this game interesting shoot me an email and let me know what strategies worked for you.

For a second opinion on the laser vs missile question with very different conclusions see Rocket Punk's math Battle of the Spherical War Cows: Purple v Green and Further Battles of the Spherical War Cows. Rocket Punk provides the following very approximate7 equation for the number of missiles a laser can destroy K = 1750 \times P \times D / (L \times V)

The parameters are:

- K is number of incoming missiles (kinetics) the laser can destroy before one missile hits the lasers

- V is the closing rate of the of the missiles (km/s)

- P is beam power (megawatts)

- D mirror diameter (meters)

- L wavelength (nanometers)

This equation determines the time it takes the missiles to reach the laser and then determines how many missiles the laser can hit before this time is up. Thus, if K=4 and you only launch 4 missiles the laser is safe, but if you launch 5 missiles, 4 missiles are destroy and 1 missile hits the laser.

This equation does not consider the problem of hitting maneuvering missiles. This is a reasonable assumption for Rocket Punk to make to given particular missile and laser capabilities. For instance if a missile can't change its position more 10 meters within the latency imposed by light and the laser beam width is 10 meters then maneuvering provides no benefit to the missile. This implies you would need greater than ~1g acceleration5 at ~0.5 light seconds (~150,000km) or greater than 15,000g acceleration6 at 0.01648 light seconds (4,940km) for maneuvering to increase the missiles chance of surviving assuming a laser that can destroy missiles when its width is 10 meters.

Thus, if maneuvering matters or not really comes down to the distance at which the missiles warhead is effective, the maneuvering acceleration of the missile and the effective range and power of the laser.

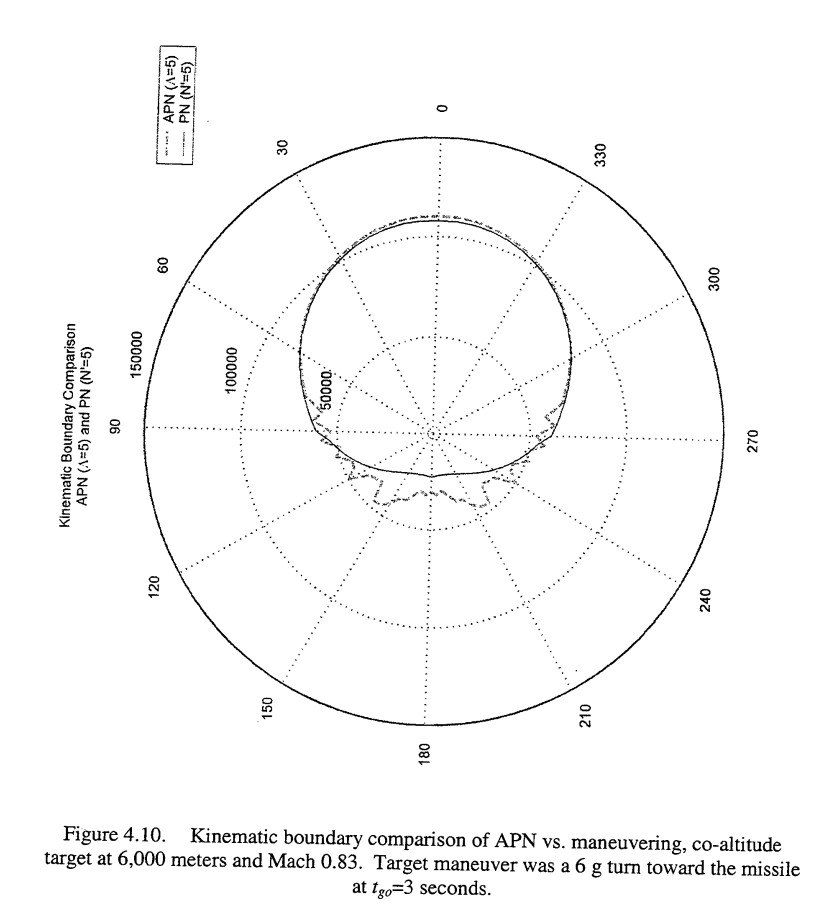

-

The missile has to be going very very fast. Whatever platform launches the missile has to be far enough away that the target ship can't just hit it with the laser prior to launching. Space is mostly empty and cool so a missile launch is going to visible to anyone looking3. Against a slow moving missile that is far away the best strategy for the ship to change course and prevent the missile from intercepting it. In aerial combat this is sometimes called a "kinematic defeat" of a missile and course changes to evade a missile is called "notching". As stated in A Method of Increasing the Kinematic Boundary of Air-to-Air Missiles Using an Optimal Control Approach (2000) a "missile's kinematic boundary can be described as the maximum theoretical range at which it can intercept a target." In space things are much worse for the missile since the missile must deal with high latency imposed by the huge distances between a ships change in course and when the missile learns about that change. The missile needs an enormous velocity advantage over the ship to launch far away and still get within a ship's kinematic boundary.

. ↩

. ↩ -

An implicit assumption I am making here is that missile can destroy the ship with the point defense laser while still being very far away from the ship. This is because if the missile needed to get as close as say 1 km away, the missile wouldn't stand a chance. Light travels 3 km in 10 microseconds, so the point defense laser would be using targeting information that is only 20 microseconds old. If the missile's warhead is say a nuclear pumped x-ray laser, or nuclear shaped charges then the missile can detonate at extreme ranges (1000 km). Thus, the range at which the missile warhead if can destroy the less maneuverable ship would be greater than the range at which the laser can reliably always hit the missile. ↩

-

" If the spacecraft are torchships, their thrust power is several terawatts. This means the exhaust is so intense that it could be detected from Alpha Centauri. By a passive sensor. The Space Shuttle's much weaker main engines could be detected past the orbit of Pluto. The Space Shuttle's manoeuvering thrusters could be seen as far as the asteroid belt. And even a puny ship using ion drive to thrust at a measly 1/1000 of a g could be spotted at one astronomical unit." Detection in Space Warfare - There Ain't No Stealth In Space, Rocket Cat ↩

-

An interesting simulation of missile to missile interception with latency "The simulation examines the effect of an accelerating target attributed to powered flight and aimpoint displacement caused by a shift in tracking point from the target plume to the payload when resolution occurs. The kill vehicle minimum requirements as indicated by the simulation include a lateral acceleration capability of four times the target acceleration and a guidance system yime constant that is less than one-tenth the estimated flight time." KILL VEHICLE EFFECTIVENESS FOR BOOST PHASE INTERCEPTION OF BALLISTIC MISSILES by Bardanis (2004) ↩

-

There are published videos of the US made Exoatmospheric Kill Vehicle (EKV), a space anti-missile missile, taking off and then hovering on Earth. This means that at minimum we already have missiles with greater than 10m/s^2 maneuvering acceleration. ↩

-

We have built guided projectiles that can withstand on the order of 15,000 Gs along one axis for brief periods. "Using the Student's t-test, the average values shown in table 1 are consistent with the Excalibur environmental specification: 15800-g's set back, 4052-g's set forward, and 3962-g's balloting. However, since the maxima values are outside of the 99% range, the distribution of acceleration maxima is not a normal distribution." Technical Report ARAET-TR-05008 - DESIGN ACCELERATIONS FOR THE ARMY'S EXCALIBUR PROJECTILE by J. A. Cordes, J. Vega, D. Carlucci, R. C. Chaplin ↩

-

Rocket Punk's equation only makes sense for reasonable values. For instance, given an mirror infinite size and the weakest possible laser power, it predicts such a laser would destroy an infinite number of missiles. This equation should be understood as a useful short hand that requires choosing values with care. ↩